Love and the Gods

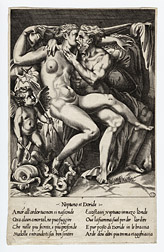

Caraglio's Loves of the Gods

This image and the next two (C631-C632) derive from the influential Loves of the Gods engraved by Gian Giacopo Caraglio in Rome, ca. 1527. They were previously owned by the painter Sir Thomas Lawrence, and when Christie's sold his great collection (May 10, 1830) the set of twenty was offered as by Caraglio himself; in fact the Chicago sheets come from a French copy attributed to René Boyvin or (more likely) Pierre Milan. Early copies integrate the image and the verse commentary into a single plate—the originals were printed from two plates simultaneously, leaving a conspicuous inky joining-line—and replicate the numbering added to the second state. The paper is French or Flemish, with a clear watermark (the monogram PS on a crowned escutcheon, Briquet 9667) indicating production in Arras, 1539 or Paris, 1541. The identical paper was used for another brilliant French copy of an engraving by Caraglio, the Adoration of the Shepherds after Parmigianino.

As in the notorious Modi by Marcantonio Raimondi after Giulio Romano, this series of erotic scenes sometimes displays the genitals openly and sometimes invents postures that conceal them, as here. The same publisher, Baviera, seems to have commissioned both sets. The design of the Loves of the Gods was initiated by Rosso Fiorentino, continuing his successful collaboration with Caraglio. After Rosso stormed off (according to Vasari) Perino del Vaga composed some of the rest, though we cannot be certain which. The default ascription to Perino should be challenged; Rossoesque elements appear throughout, and Caraglio himself may have completed the set using hints from both artists.

Amorous encounters between gods and mortals or nymphs appear in several of the ancient reliefs and cameos recorded in the Speculum, for example A132, A133, C621, C624. The Loves of the Gods engravings emulate their flattened frieze-like composition and play variations on their seated posture, adding the "slung leg" gesture that came to signify sexual invitation. Ancient sculpture also provided the attendant Cupid (e.g. A146, B393, C623, C742, C793, C797, C848 ), who here looks put-upon since he has to hold Neptune's trident as well as his own bow. Desire is signaled more by the electric hair than by the facial expressions, which remain detached and statuesque. (The helmet of wind-swept hair became a signature of Rosso's style after he moved to Fontainebleau, and Vasari identified the "abstracted gaze of the figures" as one of his distinctive innovations.) These elegant figures seem to be rehearsing a love-scene rather than succumbing to passion, despite the poem's allusion to the fire of love burning in the cold ocean. This sense of artifice is doubled by having the sea-nymph Doris hold up the backdrop.

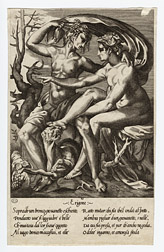

Bacchus

Many scenes from the life of Bacchus, and the orgiastic ceremonies of his worshippers, survive from Antiquity. The Speculum contains several engravings that record Bacchic motifs ( A91, A122, C626, C627, C664, C892 ) or invent new ones ( B296, B312 ), some illustrating the Latin proverb "Venus grows cold without Ceres and Bacchus" ( C628, C629 ). Caraglio depicts a relatively obscure episode, when the wine-god seduces Erigone by first appearing as a delicious crop of grapes ("uve si leggiadre e belle" as the poem puts it). Erigone is caught at the moment of transformation, gazing and pointing toward the fruit (glimpsed at bottom left) yet starting to clamber onto the young god's thigh, accidentally treading on his panther.

The arc of windblown drapery recalls Titian's airborne racing Bacchus in the London Bacchus and Ariadne, now seated but retaining his earnest face and leggy form. Caraglio's scrawny, vulpine male contrasts with Erigone's voluptuous body and gemlike profile. His immediate predecessor is the agitated, wiry figure in Rosso's "Fury," another engraving designed for Caraglio—which has been convincingly explained as a parody of the central figure in the Laocoon.

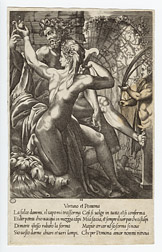

Vertumnus and Pomona

Vertumnus, a local god of seasonal fertility, came relatively late to the official Roman pantheon, so this scene is number 18 in a sequence of 20. To gain access to Pomona, goddess of the fruit harvest, he transformed himself into an old woman—but here he appears undisguised, with noble Jupiter-like features. Vertumnus's foot rests under the aroused organ of a Priapic herm, who seems alive and interested (if slightly embarrassed), holding out the triumphal palm-frond as if to reward the upcoming sexual victory. A waving line leads across the picture-frame from Vertumnus' toe to Pomona's finely-articulated hand, each toying with its spherical fruit. Her right toe, meanwhile, points towards a still-life of fig-leaves and paired apples which recreates the erogenous zones that her turning posture places just out of sight. These details emblematize the erotic relation of Vertumnus and Pomona—their bodies in dance-like proximity but touching only at the fingertips—and the artist's toying relation to the viewer, inventing ways to sculpt the front and back together by elegant manipulation of the serpentine figure. A synthesis of Raphael and Michelangelo is achieved by turning the Sistine Chapel Eve into a figure of cool and sinuous composure.

Caraglio's original engraving faithfully translates the beautiful preparatory drawing in the British Museum, London, conventionally attributed to Perino del Vaga though it closely resembles Rosso's disegni di stampe in technique, with no trace of Perino's nervous, brilliant hand. Also inherited from Rosso are the ingenious contrapposto and the contrast of deeply-engraved male and cameo-like female faces. The curved vine-arbor or berceau in the background appears again in the decorations of Fontainebleau, so may be another element that Rosso exported. In our Chicago copy, dazzling but mechanical treatment of curved cross-hatching produces a nylon-like sheen, breaking into a moiré pattern in Pomona's right hip. This recalls a work almost certainly by Pierre Milan, the Three Fates after Rosso.

Though the three Chicago Loves of the Gods came from the 1830 Lawrence sale and not from an earlier Speculum, one tantalizing piece of evidence suggests that the Salamanca-Lafreri business might have acquired these French copper-plates. One impression of this Vertumnus and Pomona, in Hamburg, bears the address `Ant Sal ex' in italics. If this suspiciously faint signature is genuine, it means that an independent French copying project found its way back to Italy and thence to the wider European market.

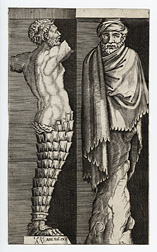

Herms and terms

Herms—square pillars topped with a sculpted head and shoulders—were another ancient feature that fascinated Renaissance designers, and also provided a window onto sexual representation since they normally featured an erect phallus or a socket to insert one. They evolved from the cults of Dionysus and Hermes and often served as boundary markers; variants with the Roman god Terminus are therefore called "terms." As in Vertumnus and Pomona ( C632 ), the herm appears in profile and defines the margin of the composition in Michelangelo's Archers ( B335 ). Herms are used to brilliant effect in the first scene of the notorious Modi after Giulio Romano, where they support the backdrop and seem to gaze longingly at the embracing couple, though unlike the version in Vertumnus and Pomona their sockets are empty.

This pair of unusual terms is number 12 in a series engraved by Agostino Veneziano, the crucial link between 1520s Roman print-making and the Salamanca shop. Agostino explored the rustic and organic origins of this figure: on the left, a sophisticated sculptured head and torso seems to sprout from a palm trunk (on crocodile feet), while on the right the entire body is formed by a draped tree stump.

Agostino was probably the engraver who preserved and revived the Modi designs by issuing his own copies ca. 1530. The discovery of a Salamanca signature on one impression of C632 (see previous) raises an intriguing possibility: perhaps Lafreri inherited sets of erotic plates, available under the counter alongside the more respectable Speculum?

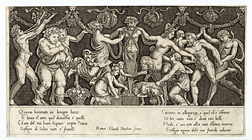

Bacchus meets Priapus

The herm moves from the margin to the center of this endearing Sacrifice to Priapus, probably designed by Giulio Romano and certainly engraved by the Master of the Die (active ca. 1525-1560, perhaps Bernardo Dado, identified by the dice marked with a B in the lower right corner). This engraver, who has even been identified as a bastard son of Marcantonio Raimondi, formed another essential link between the Raphael workshop and the Speculum. The verse inscription is identical in form to those of the Loves of the Gods, an ottava rima stanza that conveniently divides into two blocks of four lines across the plinth-like base.

As the poem makes clear, this frieze depicts the ceremonial conjunction of "benign Bacchus" and Priapus, the phallic god who guarded gardens. The drunkenly smiling and well-endowed herm is crowned with grape leaves. The worshippers include Silenus, maenads and nubile youths as well as fauns and satyrs, while their offerings include fruit and wine-jugs as well as a goat. The handsome, fit-looking Faunus brings his hand close to the member of the ephebe behind him, while making intense eye-contact with the satyress who turns toward him. The phrase belli Modi in the poem might hint at these conjunctions. Yet the effect is not at all pornographic: the close, careful burin work, the shadow-line that separates the figures from the ground, and the static, sculptural treatment of bodies in movement, all create the look of a modern antique, a miniature bas-relief carved in semi-precious stone.

For a more detailed description see Evelyn Lincoln's Itinerary.

A sideways glance at the Laocoon

This was of course the most revered of the sculptures unearthed in the early sixteenth century, all the more so since it could be identified with a masterpiece praised by Pliny. Yet the exploratory wit of contemporary artists also made parodies of this tragic composition. In a bizarre engraving known as the "Fury" the team who invented the Loves of the Gods—Rosso Fiorentino and Gian Giacopo Caraglio—convert Laocoon into a flayed-looking, maniacal figure who seems to struggle with the serpents of his own extreme imagination. The core elements of this figure then reappear in Bacchus and Erigone (C631 in this Itinerary): the strained, straddled posture, knotty torso and raised right arm, whose precise angle varied according to the different sixteenth-century restorations. (See Nicole Bensoussan's Itinerary.) A woodcut by the Venetian engraver Nicolo Boldrini, sometimes associated with Titian, preserves the entire composition but replaces the heroic humans with apes.

The author Pietro Aretino, who played a major role in the dissemination of erotic imagery and wrote sonnets on the Modi, used the Laocoon as the model for a spectacular orgy (Ragionamenti Day 1). A senior prelate of the church, sandwiched between a nun and a young male acolyte, is gripped in the convulsions of desire just as the priest Laocoon, flanked by his two sons, is crushed by the serpents. At the climax his face takes on "the frowning look of that marble figure in the Belvedere." Aretino does not intend to ridicule the original, which he praises in his poem Marfisa for its emotional power. Rather, the effect is to make desire monumental.

Apollo and Daphne

The "Loves of the Gods" were the very first subjects of human art, according to the poet Ovid: the tapestry-weaver Arachne, challenging the goddess Minerva to a competition, chose exactly this theme—and for her hubris was turned into a spider. Caraglio's series matches the list of amorous "crimes" that Arachne wove. Similar cycles were invented to decorate the walls of villas and palaces, the most influential being the love-nest built on the Tiber by the powerful banker Agostino Chigi (now known as the Farnesina after later owners). Between 1511 and 1519 Chigi commissioned amorous-themed mural paintings from Peruzzi, Sebastiano del Piombo, Sodoma and Raphael. The interior, which survives in excellent condition, includes a loggia dedicated to the love-story of Cupid and Psyche; engravings made from Raphael workshop drawings, by Marcantonio, Agostino Veneziano, Caraglio and others, disseminated these images widely (see Speculum B311, a detail of Juno, Ceres and Psyche). The outside was also painted, though all but a few figures have disappeared. These exterior scenes probably included Mars and Venus caught in an illicit embrace, Pasiphae seducing the bull, and four panels narrating Apollo's frustrated love for the nymph Daphne, captured in a set of four engravings apparently by the Master of the Die (signed with a one-spot dice without the B).

The first of these Apollo and Daphne plates made its way into our Speculum. We already saw how the Master of the Die combined a classicizing composition by Giulio Romano with the eight-line verse commentary used in The Loves of the Gods (Sacrifice to Priapus, B296 in this Itinerary). Here the designer is probably not Giulio but Baldassare Peruzzi, the original architect and decorator of the Villa Chigi-Farnesina. In this narrative sequence, as in allegorical plates such as B300, the Master sticks closely to the vertical format of Caraglio's series. Though Apollo appears triumphant in the foreground, slaying the monster Python, the real story begins in the background, where he incurs the wrath of Cupid by mocking the little boy trying to handle a grown-up weapon. In revenge, Cupid fires a golden arrow into Apollo's heart and a leaden arrow into Daphne's, making her indifferent to the god's advances. The following scenes show the famous outcome, which also appears as number 11 in Caraglio's Loves of the Gods: as Daphne flees she turns into a laurel tree, perpetual symbol of unconsummated desire transformed into art.

Cupid and Psyche

The myth of Cupid's love for the mortal Psyche, "soul" in Greek, appeared very late in Roman literature, and so comes at the end of Caraglio's Loves of the Gods (number 19, just before the closing image of Venus and Cupid asleep). This novel-length story of thwarted, enduring and ultimately successful love was enshrined in the generative space of the Villa Chigi-Farnesina, designed by Raphael and painted by a team that included Giulio Romano (1518-19). Within a decade, Giulio had designed the erotic print-series I Modi and the resplendent frescos of the Palazzo Te in Mantua, where the story of Cupid and Psyche fills one of the most important rooms. Meanwhile, an illustrated book of 32 scenes from the Psyche cycle was engraved by the Master of the Die and Agostino Veneziano, adapting the eight-line verse caption to a more horizontal format than that of the Loves of the Gods and Apollo and Daphne (C630, C631, C632, B301 in this Itinerary). Though this ambitious series is vaguely associated with Raphael, the exact artist is uncertain: maybe Giulio, maybe the "Flemish Raphael" Michiel Coxie (who designed his own Loves of the Gods engravings), maybe Perino, who later reprised it in decorations for an apartment in the Castel Sant'Angelo.

The Chicago Speculum contains 17 sheets from a Salamanca reissue, perhaps the one retouched by Francesco Villamena ( B317 - B333 ). They show the various trials imposed on Psyche by the jealous goddess Venus, who wants to break off her son's liaison but who eventually blesses their marriage and Psyche's elevation to godhead. The challenge for the designer was how to depict Cupid, normally a mischievous winged boy, as a youth old and real enough to marry a flesh-and-blood woman. Here, he has simply scaled up the putto-figure, leaving him improbably pudgy.

Cupid and Psyche: the wedding

This much-used engraving by Giorgio Ghisi accurately depicts the couple reclining on their nuptial couch, as shown in the monumental Sala di Psiche in the Palazzo Te, Mantua. Giulio Romano's fresco doubled the Cupid-figure, enlarging the bridegroom into a glorious young man but nestling a smaller amorino against Psyche's flank, a (protective?) arm between her thighs. Around them, the gods gather for the wedding banquet, while nymphs set the table and satyrs interfere; this room is literally a pantheon, with all the deities who elsewhere feature in their own stories of uncontrollable appetite - Apollo, Bacchus, Silenus, Mars and Venus, Vulcan, Pomona, and Jupiter himself, shown (with striking genital realism) about to conceive Alexander the Great. The entire scene, except for the bride and groom depicted here, was refigured into an extraordinary triple engraving by Diana Mantovana, the daughter of Ghisi's teacher and one of the few women artists in sixteenth-century Italy. See Evelyn Lincoln's Itinerary for an authoritative account of this independent Feast of the Gods (A147, A148, A149).