Castel Sant'Angelo: A Military Itinerary Through Rome and the Speculum

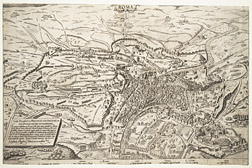

Map of Rome

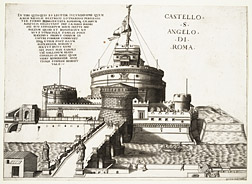

Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome was probably the most visible and frequented of European fortresses.[1] Guarding the only wholly-surviving ancient Roman bridge, which connected the papal compound of the Vatican to Rome itself, the citadel confronted every single pilgrim who visited the city and who wanted to worship at the presumed site of Peter's tomb. Coming from Rome, the pious tourist would pass through the gateway formed by the statues of Peter and Paul, but this welcoming duo were followed by the looming and glowering round tower that formed the Vatican side of the bridge, where the visitor would pass through the military checkpoint and take a sharp left turn towards Saint Peter's ( A26 ). Further linked by a separate wall to the papal palace, Castel Sant'Angelo served as a place of last resort. When Pope Clement VII took refuge there in 1527 during the siege of Rome the entire Christian world, Catholic and Protestant, became acquainted with the appearance of this military structure through the published broadsheets that reported on the conflict. Its massive cylindrical form, incorporating the tomb of the emperor Hadrian, came to symbolize Rome itself in countless paintings and engravings.

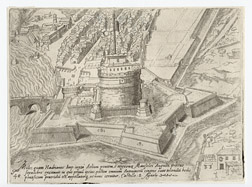

Castle of Sant'Angelo (1559 - 1565)

The medieval citadel, partly strengthened during the fifteenth century, was to have been thoroughly modernized by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, the architect of the Florentine citadel, commissioned by Pope Paul III Farnese. The fortification experience of Antonio's older relatives evidently guided him: extant drawings by Giuliano and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder come close to the condition of the Castel Sant'Angelo. The younger Antonio's project (1542-46) was to transform the late fifteenth-century bastions that had been built by Pope Alexander VI Borgia in the attempt to protect Rome from the French invasion of 1494. It was intended to double the fortification belt around the core of the citadel composed of Hadrian's tomb, and to rectify the road passing from the bridge to Saint Peter's, removing existing obstacles and achieving as much symmetry as the site allowed.

Views Of Ancient Rome (1569)

The complexity of the situation on the ground can be read from Antonio's drawings. As Nicholas Adams shows, he proposes several solutions with little relation between them―triangular, rectangular, rhomboidal, hexagonal as well as pentagonal fortresses.[2] The ambivalent relation of the fortress to Rome, even more complex than that of the equivalent Florentine citadel, made resolution difficult: the citadel was a daily reminder for the local population of the tense and often fraught relations between the papal government and the oligarchic city council. None of Antonio's projects was realized, but they clarified one part of the citadel's identity: he would have enlarged the medieval castle about four times, introducing a city-sized building as a hinge between Rome and the Vatican suburb. Evidently, the papal initiatives to fortify Rome were torn between direct concern with the Vatican and a citadel which would have symbolized too clearly the need for protection―not only from outside the city but also from the two distinct parts of Rome.

Castle Of Sant'Angelo (1575 - 1586)

It is on this important foundation of graphic studies and strategic discussions for the citadel by Antonio da Sangallo that the actual pentagonal reconfiguration of Castel Sant'Angelo was carried out by the military architect Francesco Laparelli between 1561 and 1565.[3] This architect gained great renown for his fortification of Valletta on the island of Malta, but in Rome he was part of the last important sixteenth-century wave of Florentine influence. The fortress of Rome thus benefited from the earlier Medici sponsorship of the citadel in Florence. By the time it was built, however, the Castel Sant'Angelo had a stronger competitor for attention in the citadel of Turin, which was built simultaneously, and completed earlier. Of the three the citadel of Rome had the most distinguished life in print, reaching a wide audience of religious tourists, as well as military officials.

Castle Of Sant'Angelo (1581 - 1586)

The newly fortified citadel became an important subject for the illustrations of Rome, in plans and views, which were produced for pilgrims' purchases. The citadel thus has a significant life in visual culture, where it is often illustrated out of scale, even larger than its actual size, dominating the vulnerable bridge―the connecting link between Rome and the Vatican. In sixteenth-century views of Rome, the fortress looms large; matching the scale of Saint Peter's and the Vatican palaces, it dominates the urban topography. Foregrounded by its proximity to the spiritual center of the city, it is the only secular structure illustrated in the widely disseminated view by Lafréri. Beside the illustrations of Saint Peter's, the citadel of Rome is the only building in the city, ancient or modern, to receive extensive attention in printed illustrations.

Castle Of Sant'Angelo (1590 - 1591)

The Castel Sant'Angelo combined the functions of multiple urban buildings, and displayed multiple layers of Roman history. Its cylindrical core resembled the tomb of the Metella (A49, C432 ) and that of Augustus ( B282 ); but in ancient Rome, the castrum of the Praetorian guard ( A30 ) served as the de facto fortress of the city. In the Renaissance it functioned as a palace with important decorated state and private rooms, but also as a defense installation, serving as vault, crowd-control obstacle, and customs' house. As a papal site it was dedicated to the archangel Michael, just as its individual bastions were dedicated to saints and architects. Beyond the published images, which clarified these functions abroad, the guides to Rome enumerated the treasures guarded within its confines. As late as the eighteenth century the citadel was portrayed, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi for example, with its abundant ammunition proudly displayed in its court.

Views Of Rome And Of Other Cities And Places (1600)

The new pentagonal fortress distanced "modern" geometrical design from the time-honored permutations of the square and the circle inherited from antiquity and Middle Ages. In the Castel Sant'Angelo the new citadel literally incorporates and goes beyond the cylindrical mausoleum and the medieval four-sided, turreted enceinte; its appearance is a cross-section of its troubled history ( C430 ). The rhetorical function of its graphic representation underlines the great size of the installation; the exaggerated dimensions are meant to illustrate a lack of continuity between the fortress and the surrounding buildings of the Vatican suburb. The old round tower within the new polygonal bastions became an emblem of military-architectural prowess, displayed on foundation medals and recreated in mock-sieges and fireworks that celebrated victories. In B182 the towering dominance of the superstructure is underlined by the Vatican loggie that are allowed to loom in the distance. The configuration of Castel Sant'Angelo―a more-or-less regular bastioned polygon with its fifth side completed by a waterfront―was imitated elsewhere. Examples include the Tower of London (again embracing a formidable older castle), and the fortification of ports such as Pesaro on the Adriatic, or Candia in Crete.[4] Thus the eventual design of Castel Sant'Angelo recapitulates the history of "ancient" and "modern" geometry.

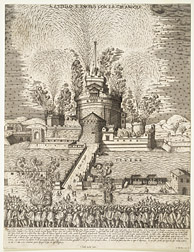

Views Of Rome (1610)

The papal functions of Castel Sant'Angelo included service in times of peace and celebration. Biringuccio, the earliest writer to write about fireworks (in his military treatise), describes the most famous design of this exhilarating form of early modern entertainment, the Girandola. Turning the fortress into a beacon of fire ( A40 ) watched by great crowds from the safety of the other shore, it was used to celebrate papal coronations (with the earliest fireworks ignited in 1481), and subsequently associated with the Castel Sant'Angelo, which acted as the fireworks' machine.[5] Thus one of the most significant urban fortresses―and one of the most visible experiments with the pentagonal citadel―was also the most prominent pyrotechnic site. The Girandola, equally celebrated as the Roman candle, shot upward in a long trail of light, exploding into a bright ball in the air and then fizzling slowly downward like a gentle rain of fire. Spinning, shooting upward, and showering down, these set pieces of fireworks design incorporated contrasting directions, speed, and light quality, implying the ambivalence of this visual artefact. Together with the Catherine wheel and the rocket, this design has survived in the contemporary vocabulary of fireworks display―a continued reminder that, through the adoption of artillery for war and peace activities, defense, destruction and illumination come to be linked in the popular urban imagination. In C545 the halo of smoke from the fireworks turns the fortress in to a "glory" that resembles the religious imagery of counter-Reformation art.

Castel Sant'Angelo (Hadrian's Mausoleum) (1621)

As the site of a repeated ludic event, Castel Sant'Angelo is the modern equivalent of other military entertainments, revivals from antiquity or strenuously cultivated medieval inheritances. A military itinerary of the Speculum would include the joust in the Belvedere court ( A67 )―between the Vatican palace and the papal Villa Belvedere―which turns this magisterial architectural site into an amphitheatre for highly choreographed military conflict. This balletic entertainment takes place in the enclosure framed by Bramante's corridors, and is accompanied by fireworks joyously exploding from the heights of the Belvedere villa. The view documents an important moment in the history of this "architectural" garden, whose axial and tiered composition would be disrupted by the insertion of the Vatican library during the reign of pope Sixtus V. The theatrically framed and large outdoor space, echoing the ancient Roman circus known to have been on this site, would have further reminded the educated audience of Claudio Duchetti's illustration of the "naumachia," the naval battle ( A44 ), which reconstructed an ambitious form of another ancient Roman entertainment. In its specially built amphitheatre, the flooded arena held a multitude of boats, festively rigged-out and gamely educating a large public in the rudiments of military engagement at sea.

Strong house, entertainment center, and monumental historic building, Castel Sant'Angelo's ample presence in the graphic record clarifies its centrality in the imagination of Rome's inhabitants and tourists.

Notes

[1] Piero Spagnesi, Castel Sant'Angelo, la fortezza di Roma. Momenti della vicenda architettonica da Alessandro VI a Vittorio Emanuele III (1494-1911) (Rome, 1995); Francesco P. Fiore, "Rilievo topografico e architettura a grande scala nei disegni di Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane per le fortificazioni di Roma al tempo di Paolo III," in Il disegno di architettura, ed. Paolo Carpeggiani and Luigi Patetta (Milan, 1989), pp. 175-80; Paolo Marconi, "Contributo alla storia delle fortificazioni di Roma nel Cinquecento e nel Seicento," Quaderni dell'Instituto di Storia del''Architettura 13(1966): 73-9; 103-30.

[2] Nicholas Adams, ed., Architectural Drawings of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and His Circle (New York and Cambridge, Mass., 1994), v. 1: 61-74.

[3] Spagnesi, pp.14-48, offers a detailed discussion of the context for the planning of the citadel's reconstruction, tightly meshed in with papal expansion plans and new roads.

[4] See Enrico Guidoni and ngela Marino, Storia dell'urbanisitica: Il Cinquecento (Rome and Bari, 1982), p. 212; Palmanova, fortezza d'Europa, 1593-1993, exh. cat., ed. Gino Pavan (Venice, 1993), p. 540, no. 49.

[5] Vannoccio Biringuccio, De la Pirotechnia (Venice, 1540), 'Fochi d'allegrezza' a Roma dal Cinquecento all'Ottocento, ed. Lucia Cavazzi, exh. cat. (Rome, 1982), and Kevin Salatino, Incendiary Art: the Representation of Fireworks in Early Modern Europe (Santa Monica, 1997).