The Eternal City: Maps of Rome in the Speculum

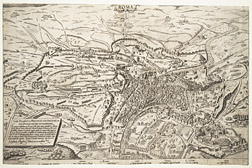

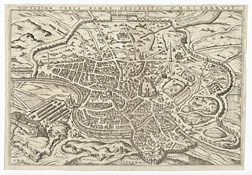

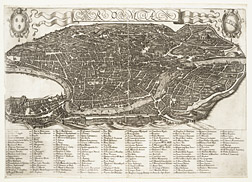

Renaissance Rome from the North

Dated January 1, 1561, this evocative bird’s-eye view by Giovanni Antonio Dosio shows an idealized view of Rome from the north, the direction from which countless travelers approaching the city by land first laid eyes upon it. Although no viewer could have enjoyed such a complete panorama of Rome in the early modern era, Dosio’s perspective corresponds to a plausible vantage point from the hills north of the city.

The map provides a vivid glimpse of mid-to-late sixteenth-century Rome, which is demarcated from the surrounding countryside by the third-century Aurelian walls. At the bottom of the map, the ancient Via Flaminia provides a viewer’s entry into the image, through the Porta del Popolo, the northernmost city gate. At lower right are the Castel Sant’Angelo and the Vatican, which together comprise a large, fortified complex centered on the New St. Peter’s, construction of which had begun in 1506. Michelangelo’s famous dome is shown in progress, but the basilica would not be capped by its defining feature for nearly three decades.

Within the Aurelian walls, the Tiber snakes through the densely populated city center, where anonymous structures flank recognizable monuments such as the Pantheon and the Capitoline hill (or Campidoglio). Farther from the river, the closely packed buildings give way to pastureland dotted by crumbling aqueducts and hulking ruins, such as the Colosseum and the imperial bath complexes. These ancient monuments had remained in place as the city shrank away from them following its height in the late Roman Empire. Populated areas, which had once stretched to every corner of the walls, were, by the late Middle Ages, clustered close to the Tiber, leaving a vast green belt known as the disabitato (or uninhabited zone). Still, Rome was on the rise when this map was made, having tripled its population in the previous 150 years.

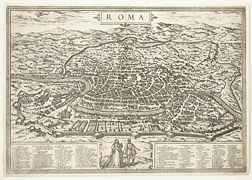

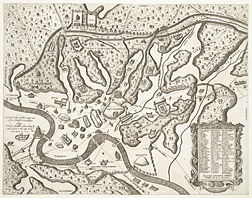

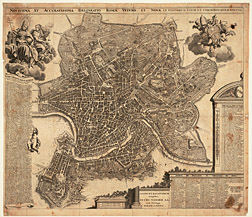

Renaissance Rome from the Janiculum Hill

While the previous map depicted Rome from the north, this engraving shows it from the west, specifically from above the Janiculum hill. (The orientation of city maps was not fixed in this period, and it was not until the eighteenth century that it would become standard to place north at the top.) This orientation was the most common for images of Rome well into the 1700s, for reasons having to do with the city’s topography. Although not one of the original seven hills, the Janiculum is the highest point in Rome, and to this day it remains the best place from which to enjoy a panorama of the city from any point on the ground.

This map, which appeared in the Civitates orbis terrarum (1572-1618), a massive compendium of cities published in Cologne by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, was one link in a long, winding chain of copies and derivatives of a 1555 prototype by Ugo Pinard. Perhaps it is poetic justice that this rendition would find its way back into the Chicago Speculum, for Pinard’s original had been published by none other than Lafreri.

But the pedigree of this map speaks to a more positive trait, as well—that of international collaboration and cross-pollination. Not only did the prototype published by Lafreri eventually make its way north of the Alps and back, but those who contributed to its publication came from all over Europe. Ugo (or Hugues) Pinard, for example, was a native of Chalon-sur-Saône, Burgundy; the engraver of his 1555 map, Giacomo (or Jacobus) Bos, was Flemish; Lafreri himself was, of course, from Besançon. All were foreigners who worked together in Rome to export an image of Rome, only to re-import it back to Rome in the end.

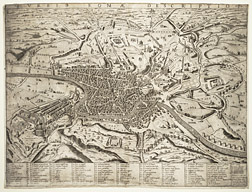

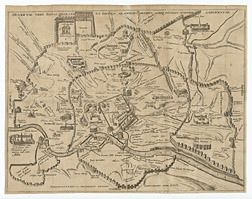

Rome circa 1590

This map is a 1602 reprint of a prototype engraved by Ambrogio Brambilla and published by Claudio Duchetti (a.k.a. Claude Duchet), Lafreri’s nephew and successor, in 1590. Brambilla’s map, like the previous one (A3), shows Rome from a vantage point high above the Janiculum, but it reflects important transformations to the city that had occurred in the intervening decades.

At lower left, the dome of St. Peter’s, completed in 1590, rises high above the Roman cityscape. The Vatican obelisk, which had stood on a site adjoining St. Peter’s for 1,500 years, now towers above the piazza in front of the church, having been moved there—with great difficulty and fanfare—in 1586. To contemporary viewers, these were potent signs of Rome’s “rebirth” as a modern Christian metropolis, rising over the ruinous foundations of its ancient counterpart.

Even more striking are the infrastructural developments. In the late 1580s, Pope Sixtus V initiated an urban planning project of unprecedented scope. In this, he was following on the heels of papal forebears who had begun to impose order on Rome’s medieval warren by laying out new, straight streets, such as the grand trident radiating from Piazza del Popolo (at left in the map). Sixtus, in turn, focused his efforts on the vast blank canvas of the disabitato, creating a star-shaped network of long, straight streets radiating from the remote basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore (visible in the upper-central quadrant, numbered 11)—the centerpiece in his grand plan to bind the city together. By using new thoroughfares to link the major basilicas, Sixtus not only catered to the needs of the pilgrims who swarmed to Rome in Jubilee years, but he also laid the groundwork for Rome’s population to expand into previously deserted areas of the city.

Rome circa 1590, redux

Published in Frankfurt in 1597, this map was based on a prototype by the same author, and from the same year, as the previous one (A5). The two maps are closely related and resemble each other in many respects. But one subtle difference—the treatment of the ancient Capitoline hill (or Campidoglio) that appears just to the right of center in each map—serves as an important reminder that these images were not necessarily faithful reflections or “mirrors” of the contemporary Roman cityscape. In the previous map, Brambilla showed the Campidoglio correctly oriented toward the left (i.e. north); here, it is turned frontally toward the viewer, literally putting its best face forward. Its size has also been inflated in proportion to that of the Colosseum (behind and to the right of it), a maneuver that serves to exaggerate the prominence of this Renaissance monument with regard to that of the ancient structure. This inaccuracy is hardly a mistake; instead, it is the artist’s nuanced way of asserting the triumph of modern over ancient Rome. (For more on the Campidoglio, see Rebecca Zorach’s itinerary.)

Clearly, then, artists took creative license in these maps, which brings up another important point, regarding function. While most modern city maps serve as wayfinding tools, none of the maps discussed in this itinerary were intended for the utilitarian purpose of navigating city streets. Instead, they were meant to commemorate, in visual form, the abstract idea of “Rome reborn.”

The Ancient City through Sixteenth-Century Eyes

Mapmakers also turned their efforts to recreating visions of ancient Rome, whose vanished grandeur, hinted at by the impressive ruins that dotted the cityscape, loomed large in the imagination. The shortcomings of these images as archaeological reconstructions are sometimes lamented by modern scholars, but they are invaluable records—if not of Roman antiquity itself, than of Renaissance perspectives on it.

This map of the ancient city, like the previous two showing contemporary Rome (A5 and B287), was the work of Ambrogio Brambilla. It includes just a handful of monuments in reconstruction, rising like monoliths on a largely deserted cityscape. At lower left, the vanished Circus of Nero occupies the Vatican hill; above it, the Castel Sant’Angelo is restored to its original form as the Mausoleum of Hadrian. The Colosseum appears fully intact toward upper right, above the enormous Circus Maximus, resuscitated along with several other ancient sporting venues. The imperial bath complexes, accompanied by long stretches of aqueducts, sprawl across the hills. Many of these details were conjectural and erroneous, but as emblems, they capture vividly the Renaissance notion of a magnificent ancient city, defined by monuments and topography alone.

Mapping Layers of Roman History

Dated 1600, this map by Paulus Merula superimposes various incarnations of the ancient city across several important periods in its development, capturing Rome’s identity as an urban palimpsest.

To a significant extent, Merula borrowed from an earlier map of 1552 (not included in the Chicago Speculum) by the antiquarian/architect Pirro Ligorio. Merula removed most of Ligorio’s references to Renaissance Rome, and he expunged the many anonymous buildings that his predecessor had used to suggest urban density. In this way Merula created a city populated only by monuments, its splendor undiluted by the countless modest structures that must have catered to everyday needs of habitation and commerce in antiquity.

Merula also enriched Ligorio’s prototype, inscribing upon it earlier eras in Rome’s urban history. Within the third-century Aurelian walls, which are largely intact to the present day, he depicted the fourth-century BCE Servian circuit that preceded them in the Republican period, bits of which still exist. Within the Servian walls, in turn, he showed the square plan of the original Romulan city, known only from legends of the founding of Rome, to the right of the Capitoline hill. Merula, therefore, encapsulated more than two millennia of myth and history, physical fact and imaginative speculation, in a small two-dimensional image—approximately ten by thirteen inches.

Changing Visions of the Ancient City

While the previous two maps are distilled glimpses of ancient Rome populated only by a few famous landmarks, this one presents the city as a vibrant architectural cornucopia. Published by Goert Van Schayck, it shows monumental buildings crowding against one another cheek-to-jowl, stretching the limits of the Aurelian walls to full capacity.

Many of the familiar monuments appear, such as the Pantheon and Colosseum in the central section of the map, as do other prominent structures known only through fragmentary remains or written accounts, such as the Circus of Nero (at the bottom margin, toward the left corner) and various naumachiae (structures that resembled amphitheaters, in which simulated naval battles were staged for public entertainment; see for example the round structure just below and to the right of the key at upper left). But they are almost lost in the greater urban cacophony of insulae (ancient apartment buildings) and anonymous structures of varying sizes and degrees of individualization. In this way, Van Schayck presents an image of the ancient city as a place where people across the social spectrum actually lived and worked. Regardless of the archaeological accuracy of his map, it captures something of the spirit of the ancient capital, which had a population of over one million by the height of the Empire.

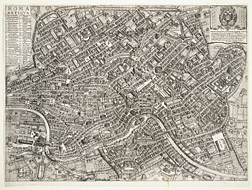

Rome on the Threshold of the Baroque Era...in Microscopic Detail

Even as many artists and engravers looked back to the ancient city, “new” Rome attracted a great deal of attention. By the end of the sixteenth century, the city’s population had rebounded to approximately 100,000. In this period of Counter-Reformation zeal, Rome was the center of Catholic renewal. New churches sprang up in a veritable frenzy of construction, artists flocked to the city to decorate those churches, intellectual life flourished (albeit with the occasional interference of the Inquisition), and pilgrims came in ever greater numbers.

In 1593, the artist Antonio Tempesta published a remarkable map of Rome that became the new visual paradigm for the reenergized city. A mural-scale engraving on twelve sheets, it was a truly monumental statement of Rome Reborn—and, as a result, much admired and copied.

This version, done by an unknown engraver several decades later, reduces Tempesta’s grand statement to a mere 11” x 16”, but still preserves an impressive wealth of detail from the original. The engraver has followed Tempesta by including just about every Roman palazzo, church, piazza, fountain, and footpath. Many prominent recent additions to Counter-Reformation Rome appear. Just to the southeast (i.e., above and to the right) of the Pantheon, it is possible to make out the Jesuit college and the Gesù, the mother church of that new and powerful religious order (numbers 120 and 122 on the map). Further to the southeast, beyond the Colosseum, the new straight streets of Sixtus V form regular axes along which new structures have already—in just a few years—begun to pop up.

The Persistence of a Paradigm

The influence of Tempesta’s magnificent map of Rome was profound and enduring. A print of such size and quality was quite costly, putting it out of reach for most collectors, but Tempesta inspired a host of imitators who answered to the wider public demand. The persistence of Tempesta’s paradigm, and the slavishness with which it tended to be copied, meant that an increasingly outdated city image continued to have wide circulation.

This German derivative, published in Augsburg by Johann Philip Steidner, dates from ca. 1700, more than a century after the original, and yet it still shows Rome ca. 1593—with no updates to reflect the dramatic changes that had transformed the urban fabric over the intervening century. In this map, made far from Rome and intended for German viewers—few of whom must have had personal experience of the city—Tempesta’s once-groundbreaking prototype lived on long after it had become obsolete as a picture of “modern” Rome.

A New Map for a New City

In 1676, a new map was published that ultimately eclipsed Tempesta’s as the foremost icon of Rome. Giovanni Battista Falda’s monumental engraving of that year was the most up-to-date and exhaustive picture of the city in almost a century. In this breathtaking bird’s-eye view, the spectator has the vivid illusion of floating far above the city; gone is the earlier conceit of a foothold corresponding to the Janiculum hill. Falda’s map is the Google Earth of the early modern period.

As is clear from this faithful (if much smaller) copy, the map provides a complete picture of the urban changes since Tempesta’s time. At lower left, Bernini’s distinctive keyhole-shaped piazza, constructed 1656-67, provides a monumental approach to St. Peter’s. The new basilica is fully complete, and even the statues of apostles that crown its façade can b discerned, if only as silhouetted verticals. Across the city, villas and gardens extend over the former disabitato. The most important churches of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries all appear—Chiesa Nuova, Sant’Andrea della Valle, Borromini’s Sant’Ivo, and so on. Rome is shown as a fully realized Christian capital. At upper left, two allegorical figures of Faith and Justice bestow their divine virtue on the city.

Along with the other maps in the Chicago Speculum, this one provided viewers with the urban context for the prints of Roman monuments, mythologies, customs, and rituals that comprised the majority of the collection. More than that, however, the sequence of maps also allowed viewers to understand the city as much more than geographical fact. Rome was, rather, a symbolically charged locus where ancient and modern, classical and Christian, reality and imagination came together and were inscribed on the very topography of the city.