Prints and Ritual in Renaissance Rome

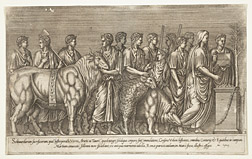

Ancient Ritual Sacrifice

This engraving shows the suovetaurilia at Rome, the combined sacrifice of a whole pig, a sheep and an ox, the principal animals of the farmer, and sacred to Mars. Like most rituals, it marked a border―in this case, the ending of the census that took place every five years with a solemn rite of purification (lustrum) made efficacious by animal sacrifice. The census involved a review of the classes and centuries on the Campus Martius, overseen by two elected patrician Censors who listed and classified the members of Roman society (knights and centuries are mentioned in the caption) so that any alien elements could be expelled. Here, a victimarius holding an axe (popa) is seen near the rear of the procession, while the censors and tabulated citizens of Rome accompany the group to where the priest stands in front of the altar. The engraver mentions that his design records a marble frieze found in a wall of a building on the Campus Martius; it is today in the collection of the Louvre.

Sacrifice To The God Silvanus

One of the oldest of the Roman deities, Silvanus was primarily a god of agriculture, woods, and boundaries―a forest spirit who had to be propitiated if woods were cleared or if his territory was otherwise compromised. Augustine, in Civitas Dei, promulgated for the Middle Ages a legend first mentioned by Varro that Silvanus was also a cruel god, who caused fever in women made vulnerable by childbirth. For this reason, groups of three men representing agricultural gods and goddesses patrolled the homes in which there were pregnant women, or women who had recently given birth, to keep Silvanus from evil deeds. The men in the foreground of this image may represent the three men whose charge it was to defend the houses of new mothers. Silvanus was also venerated at male bathhouses as a patron of male health, and later became charged specifically with the health of emperors. Offerings to Silvanus were made to his cult statue, as we see in the engraving, although later a few temples and chapels were set up in Rome in his honor. One inscription to him was found at Claudian baths that later became the Baths of Constantine. Because of the relationship between Constantine and the Bishop Sylvester (Bishop of Rome 314-355) who baptized him and also founded the Basilica of St. Peter, and also perhaps because of the similarity in the sound of their names, it seems that Silvanus became associated with the bishop saint Sylvester. Many of the inscriptions found in Rome recording offerings to Silvanus were found near the site of churches dedicated to Saint Sylvester. Images of Silvanus on ancient stone altars show him holding lilies or fruit and a pine bough, for he was also responsible for the bounty of the harvest as well as the health of farm animals. He was also connected with the gods Mars and Hercules. In this Renaissance image the statue of the god is Martial in aspect, while the lion skin and club that Silvanus holds also ally him with Hercules.

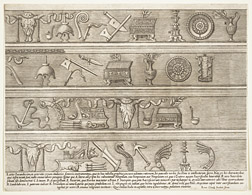

Frieze Of Sacrificial Instruments

In the Renaissance, a practical interest in ritual sacrifice extended from curiosity about the instruments and techniques of ancient worship to the exact order and history of the elements of the Christian mass, encompassing information about the odd religious practices of exotic foreigners such as Jews, Asians, and ancient Egyptians. From about the 13th century Christian scholars seemed to become interested in technical aspects of pagan blood sacrifice, which Christianity replaced with the re-enactment of Christ's death and resurrection in the ritual of the mass. At the same time, mendicant friars fanned the flames of popular suspicion in promulgating the misinformation that Jews living among them still engaged in blood offerings. Interest in ancient sacrifice arose along with new and intense veneration of the wounds of Christ, which worshippers were extolled to visualize in exact measure and detail through luridly colored woodblock prints that claimed to be life-size, and which bore captions imploring the viewer to kiss and caress them. In the 15th-century there arose a cult of the Precious Blood of Christ, blood which was supposed to have healing value, and which sparked lasting theological debate between Franciscans and Dominicans over whether or not the blood that Christ lost on earth was reunited with the godhead after the Ascension. Theological writing about the medicinal nature of Christ's blood and the humanistic study of antiquity led to curiosity about the techniques of ancient rituals of sacrifice involving blood, of which there was much visual evidence in the form of sculpture and friezes. The instruments of Christian mass (the book, bell, candlesticks, chalice, patten altarcloth, and the wheat of the Eucharistic host and the grapes for the wine) seemed to be more civilized echoes of earlier ceremonies, such as the pouring of wine on ancient altars, as well as of instruments such as the ritual axes, patellae, and other instruments whose uses were described in ancient texts by Livy, Ovid and others. Machiavelli, however, found a productive fierceness in the religious rituals of the ancients, writing that the ancients were more in love with freedom than the moderns are, because their religious institutions are more powerful, "counting first among them the magnificence of their sacrifices as compared with ours. There is more delicacy than splendour in our display, and no ferocious or jubilant action whatsoever. There was no lack of display then, nor lack of magnificence in their ceremonies, but added to it was the action of the sacrifice full of blood and ferocity, where a multitude of animals were slaughtered, which sight, being so terrible, made man behave likewise" (Discorsi sopra le Deche di Tito Livio libro II, cap. II).

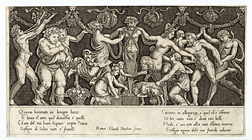

Sacrifice To Priapus

Priapus was a god of fertility, and also of gardens and herds. His cult spread from Asia Minor to Greece and Italy. In Pompeii his image was painted on entry halls, and his statue was often placed in the doorways of houses. Statues of Priapus, usually represented as a deformed man with a huge phallus, also stood as a kind of scarecrow in gardens where he protected crops from marauding animals and other thieves. It was the custom to inscribe short, humorous poems to his statue, in some of the classical verses about him he scares away thieves by threatening to sodomize them with his miraculous member. He was a son of Aphrodite, but his father may be Dionysus, Adonis, Hermes or another god. Giulio Romano, the Roman artist who made the design for this print, visualized the god as closely related to Dionysus. Here, the artist combines different ritual elements in his image of worship. The dancing figures behind the god are Maenads, followers of Dionysus/Bacchus who worshipped him through imbibing the wine made from the grapes of which Dionysus was the founder. To the left, a chubby Silenus who has greedily filled his robe with grapes, and now has exposed himself while trying to keep them safe, earns the evident approval of a lusty satyr who prepares to mount him from behind. Goats, symbols of unbridled lust, often appear in Priapic images, as they do here, and are also the usual ritual sacrifice to Dionysus. The artist shows Priapus here in the form of a herm, a pillar that usually supported the head of Hermes with a phallus below, that guarded houses and street-corners.. By darkening the background the artist gives the impression that this image, like the first one in the itinerary, was copied from an ancient frieze, which gives the scene antique authority. It is more likely to have been the product of Giulio Romano's well-informed ideation, an invention in which antique images of lusty Dionysian carousing and ritual sacrifice are brought together and enlivened through the liberal play of his own fantasia, or imagination.

Scenes From The Wedding Feast Of Cupid And Psyche

Scenes From The Wedding Feast Of Cupid And Psyche

Diana Mantovana engraved this three-sheet print from a drawing provided for her by another artist of a segment of Giulio Romano's fresco of The Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche. It illustrates the culmination of the story The Golden Ass by Apuleius (123/125-180), and was painted in the Palazzo Te in Mantua between about 1526-1528. Diana dedicated her engraving to Claudio Gonzaga, a member of the Mantuan ruling family who had a high position as majordomo of the papal court in Rome, in charge of papal meals and the kitchen (the flowery dedication appears at the bottom left corner of A147). The image combines elements of ancient celebration, such as the Silenus figure in the center of the middle print, drinking from an amphora and cuddling a small satyr, and particularly Renaissance traditions of feasting such as the important display of the family's best dishes on a multi-level sideboard. Here, the tableware of the gods is imagined as gold plate in an antique style, popularized from the many designs made available to Renaissance artists through series of engravings of fantastic vases and chalices all'antica. Satyrs serve the gods who have gathered on Olympus to bless the happy union of the two lovers, who do not actually appear in Diana's print. At the far right, Mars and Venus are seen in a bath, attended to by a cadre of industrious angels. Mars is being dressed by the bridegroom, Cupid, who is also Venus' son. In the fresco, Cupid and Psyche are central to the image, reclining nude on their marriage bed just to the right of Silenus and the table with the display of plate, and before the table signifying the more rustic banquet. Diana Mantovana abbreviated her print, leaving out the scene with the married couple which had been engraved as a separate image by Giorgio Ghisi, perhaps feeling that the ritual sacrifice of a bride on her marriage bed was an immodest subject for a female engraver. With prints such as this, which records and interprets an image made by a Roman artist who had moved to Mantua, and then been engraved by a Mantuan engraver who moved to Rome a half-century later, a courtly, Mannerist style was kept current and continually before the public eye until the end of the sixteenth century.

The Triumph Of Scipio

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Major (ca. 236-183 BCE) became a military hero primarily through his bloody defeat of Hannibal at Carthage. After the war he "sent a large part of his troops by sea while he himself made his way through Italy. Everywhere he found rejoicing as much on account of the peace as for victory, when the towns poured out to do him honour and crowds of peasants too held up his progress along the roads. He reached Rome and rode into the city in triumph―triumph such as had never been seen before." (Livy, The History of Rome, XXX: 45). Roman triumphs were fertile ground for the Renaissance imagination, combining the features of a magnificent procession with the martial glory of a marching army. The elaborately carved Imperial triumphal arches that Renaissance Romans could still see in the Forum carried evocative sculptures of bound captives and friezes showing just such triumphal entries as the one pictured here (also see prints A116, A136, B336, B337, B338, B339, B340, B341, B342, B343, B344, B345, B346, and D993). Triumphs included a rigid and highly legible hierarchy of participants that built suspense for spectators who waited for each segment of the parade to appear. They admired the captured animals, slaves, and the spoils of the looted country, such as the huge decorative urns, presumably heavy with Carthaginian silver, that strong men carry aloft in this engraving. Military trophies in the form of armor stripped from the vanquished soldiers who follow, bound and stooped over behind the rearing horses of the conquering Romans, are held up on spears, emphasizing the emptiness of the protective suit and the vulnerability of the armor-less nation (for trophies, see C607, C608, C609, C610, C611, C612, C613, C614, C615, C616, C617, and C618). Renaissance viewers were used to participating in religious or pilgrimage processions, to experiencing the royal entries that dominated whole streets when dignitaries entered the city (see #8), or to living among domestic furniture painted with allegorical Triumphs from Petrarch's poems, the Trionfi, that showed the Triumphs of Love, Death, Chastity, Fame, Time and Eternity in colorful re-enactment of antique military triumphs. The church adopted the form of military triumphs for Christian ceremonies involving the translation of the relics of martyr saints, or when Rome reincorporated into the city the bodies of important church members, such as the heart of Carlo Borromeo, which was processed into the city after his death. Viewers easily enlivened their experience of the monochromatic engravings by reading into them familiar details such as the colorful flags, the victorious trumpeting of the trombones, the clamorous marching of horses and men on the stone streets, and the shouting of spectators. Just such details and opportunities for showing riches and pageantry that this story provided made the Triumph of Scipio a favorite subject for richly woven tapestries in gold, silver and brightly colored silk threads destined for princely courts. Giulio Romano designed such a cycle of the Scipio story for the French king, Francis I, now only known through copies and drawings. Prints, tapestries and the growing reliance of the papacy on ritual meant that precisely choreographed and impressive ritual processions were objects of fascination throughout the 16th century. Print B307 is a "refreshed" version of this plate made for the publisher Philippe Thomassin, in which the lines are regularized and enriched by Thomassin or an engraver working for him, to compensate for the pale and worn character of this much-printed plate. Other scenes from the story of Scipio are shown in prints B313 and B306.

Benediction Of The Pope In St. Peter's Square

For most of the 16th century new and old St. Peter's co-existed in different proportional relationships to each other, as the old basilica (see B189) with its courtyard, outbuildings and sculptures came down and the new one arose within and behind it. The Popes continued to conduct masses there, and to preside over public events such as the one pictured here. In spite of the construction, improvements were continually made to the old complex to accommodate the performance of rituals expected by the many pilgrims who came to Rome to receive indulgences, to pray at the site of relics and martyrdoms, and as in this etching, to see the Pope and receive his blessing. At the moment the pope appears, trumpeters arrayed on a balcony to the right announce the event, riveting the crowd's attention on an arched opening distinguished by an honorific canopy, located at the center of the print, on the middle story of the Benediction Loggia. Begun during the papacy of Pius II (1458-64), the construction of the Benediction Loggia required stripping ancient marble from antique buildings in nearby Ostia and Porto. It was torn down to accommodate the façade of the new basilica at the end of the 16th century. The first version of this etching was made in 1567, and shows the bell-tower behind the loggia with a pointed spire; in 1571 that was changed to a dome shape, a modification that is reflected in this version of the print, which is an almost exact copy of the 1571 version. The print aims to show the masses of pilgrims of all classes, male and female, flocking to the city's most important piazza to receive a ritual benediction in the form of the sign of the cross, that will, the caption says, protect them from the devil. However, like the pilgrim guidebooks to Rome that not only describe the city's religious sites and events but also architectural monuments of any interest at all, this print offers the most up-to-date version of papal architectural enterprises. The pope shown here is probably meant to be Pius V (1566-1572), given the dates of the original version, but since even under magnification no identifying arms or other features specify a particular pope, this print could be commercially viable at least until modifications made to the basilica became too sweeping for the plate to accommodate the changes.

Reception Of Cosimo I By Pope Pius V.

The writing on the wall in the right-hand part of this etching tells us that "The Grand Duke of Tuscany, having come to Rome on February 18, 1570 to thank the pope for titles that had been conceded to him and to be crowned Grand Duke, made a public entry, in which he was solemnly accompanied by all the court between two Cardinals, and he was received by His Holiness in public concistory in the Sala Regia, as you see in this picture." On August 27, 1569, in spite of opposition from the Holy Roman Emperor, Pope Pius V issued a papal bull granting Cosimo I de' Medici the hereditary title of Grand Duke of Tuscany. The formal investment took place in Rome, and it was for this event that we see Cosimo entering the Sala Regia, just outside the Sistine Chapel, flanked by Cardinals and surrounded by the entire papal court. We see Cosimo twice, once as he enters the area where the pope is seated (we see him from behind, on his knees, flanked by two Cardinals with others in line behind him), and again on the stairs leading to the papal throne. An aide lifts the hem of the papal robe so that the pope can extend his slipper, which Cosimo, kneeling on a step below, leans forward to kiss. Every moment of Cosimo's entry and his audience with the pope was scripted to the last detail, and modeled after an ancient rite, the ceremony of the golden rose. Cosimo's clothing, every phrase uttered, every gesture, when to stand up, when to walk on one's knees, and when to read out loud his allegiance to the pope, was choreographed with extreme care. At the end of the ceremony Cosimo was invested with a crown from the pope, as well as a scepter and the golden rose for which the ceremony was named. Ceremonies of obeisance were carefully observed, as were all parts of royal entries, such as the one Cosimo would have made into Rome, and from the city gates to the Vatican. The papal court became famous during the sixteenth century as a model for the punctilious observance of courtly ritual. On the wall to the left Duperac shows the Medici coat-of-arms, now topped with the Grand-Ducal crown that Cosimo and his descendants had just won the right to wear. Surrounding the crown is the necklace of the order of the Golden Fleece, which Cosimo wore at the coronation, and below it an inscription relating to those qualities of Cosimo, mentioned in the papal bull, which made him worthy of the title of Grand Duke, and which appear engraved on the interior band of the crown.

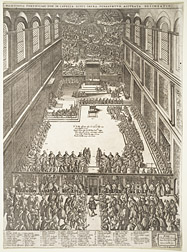

St. Peter's Basilica: Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel is the setting for the sumptuous celebration of papal mass, with a full complement of Cardinals of the church, bishops and other members of the papal curia, resplendently dressed for the occasion in their ceremonial mitres, or their red or purple hats and cloaks (as the caption tells us). They sit in hierachical order at their places beyond the carved screen that separates the privileged clergy, with direct access to mass celebrated at the altar, from the crowd outside that is eager to see and petition the pope and cardinals. The Cardinals seated along the wall to the pope's right are the most important, followed by bishops, priests, deacons, and then other members of the curial bureaucracy. This is actually an ideal scene, for the last part of the century was marked by complaints of disorder and indecorous behavior at these most solemn rites. The order of the rites for the celebration of mass were prescribed by a congregation in charge of ceremonies, and codified in an elaborate printed manual that was regularly updated. This book acted as a script for the pope and clergy to use throughout the ritual year. A Master of Ceremonies (n. 46) sits on the dais closest to the pope, since he is responsible for the smooth unfolding of the rites and maintenance of the orders of precedence that characterize the papal court in this period. At this moment, all is still as the Pope and his court listen to the Sistine Chapel choir singing from the cantoria (n. 51) at the lower right. Order is kept at the border of the inner sanctum by Swiss guards, the pope's personal protective forces. Brambilla takes care to differentiate members of the exclusively male crowd outside the gate, none of whom are identified by number, so that we can recognize tonsured monks, foppish Frenchmen, Easterners in their Phrygian caps, local dandies, pages and soldiers. In the Sistine Chapel, which served both the as the pope's private chapel and as an audience hall, tensions between the observance of royal protocol and display of church hierarchy required a special kind of diplomacy. Seated almost directly across the chapel from the pope is the secular governor of the city (n. 12), and in the middle of the long bench on the same side are the leaders of various countries who might be present in Rome and attending the mass that day (n. 10). Separated in an intermediate zone between the screen and a curtain are a group of assorted lesser noblemen (n. 20). The elevated altar with its baldacchino exactly echoes the dais containing the papal throne, so that the body of the pope is equated with the body of Christ, in its ritually re-enacted resurrection on the altar. Every person and item of ritual furniture (the altar with its book, candlesticks and crucifix laid out, the papal throne to the left with its honorific baldacchino) is numbered and then labeled in the key below, so that viewers of the print can learn every arcane detail of this aspect of the papal mass. The entire scene takes place against the backdrop of Michelangelo's fresco of the Last Judgment (n. 57), the painting that completed the pictorial program of the chapel begun during the papacy of Sixtus IV, for whom the chapel is named.

Tournament At The Cortile del Belvedere

In this print we see a medieval event, a jousting tournament, taking place in a Renaissance space, the Cortile del Belvedere, during the reign of Pius IV. The space was designed by Bramante in the reign of Julius II to connect the Villa Belvedere, (seen at top, with fireworks), built as a summer retreat by Innocent VIII, to the Vatican palace, then undergoing renovation. It was completed after Bramante's death by the antiquarian Pirro Ligorio, during the reign of Pius IV, at just about the time this print was made. Even though the cortile was part of the structure of the Vatican palace complex, it showcased many secular, and even pagan objects and events. The Villa housed (and still houses) the papal collection of antique sculpture, including the famous Laocöon (A121 and A107). Many of the larger sculptures were displayed outdoors in the formal gardens shown to the left of the Villa structure (although in reality this area is to the right of the Cortile, and reversed in this print). The architecture of the walls that make up the interior façade of the cortile is severely and unprecedentedly classicizing, showing how deeply Bramante had absorbed the techniques, materials and theory of ancient architecture, and specifically of an antique hippodrome, or garden-circus, a place for ancient games and races. As such, a tournament is less anachronistic than it first seems, especially since many chivalric forms were revived in the ambience of Renaissance courts, such as the papal court. This spectacle with plumed riders and caparisoned horses, complete with fireworks, took place on the penultimate day of Carnival. It is the day before Mardi Gras which ends the Carnival season, when the solemn period of Lent begins with Ash Wednesday. The joust was organized to celebrate the wedding of the pope's nephew, Count Jacopo Annibale Altemps, to Ortensia Borromeo. The viewing point for this print is in the Vatican Stanze, private apartments for the Pope and his court in the Vatican palace from which all the cortile could be seen in regular perspective and perfectly ordered: men and women watch from separate bleacher-like stands in the foreground, and mounted combatants line up to take their turn tilting at each other down clearly outlined diagonal paths, to clash at the center. Further from the papal window, before the ramp leading to the upper level, things get more chaotic, as viewers seem to be hurtling from the stands to the consternation of those below.