Viewing Ruins

The Ideal View

The gigantic Roman amphitheatre known as the Colosseum, begun in 75 AD, was the largest antique building surviving in Renaissance Rome. Designed to seat more than 70,000 spectators, the elliptical structure was used for gladiatorial combat and animal fighting until well into the seventh century.

By the time this print was published in Rome in 1581 by Claudio Duchetti, much of the Colosseum's western side had vanished, ravaged by fire and earthquakes, and carted away by centuries of looters―a process that was going on continued well into the 1600s. Duchetti's print, a copy of an earlier Lafreri composition, smooths out the gaping hole at the building's southwest quadrant. He uses the view to show both the interior of the Colosseum and the exterior elevation. Many printmakers were amateur architects, and the cutaway building appears less as a ruin than a scenographic plan, scoured of all but he faintest signs of age.

The print's extraction of the Colosseum it its urban setting can be contrasted with other, smaller views of the same Colosseum by Northern artists (cf. B212, B217), which often blended bits of the structure with the landscape, emphasizing its physical surroundings.

A new kind of landscape

This etching was one of twenty-four views of ancient Rome published by the Antwerp artist Hieronymus Cock (1510-1570). It shows the Colosseum glimpsed from ground level, its crumbing façade sprouting weeks and grass. The low viewpoint and tight cropping monumentalize the building, emphasizing the idea of a ruin seen, as opposed to just charted.

In contrast to other views (e.g. A29) Cock scrutinizes the decay of the archways, noting how the edges of masonry have been chipped, and how the sprigs on the lumpen ground are the same as those high up in the rotunda. Cock's print suggesting that ruination is still going on. This is an image of antiquity in the present―seven birds flutter away, and a draftsman in modern dress sketches in the immediate foreground.

Cock journeyed to Rome between 1546-8 intending to study antique sculpture, but became fascinated with the Palatine monuments, mounting expeditions to the Colosseum and the Baths of Diocletian. The drawing for this print, in reverse, survives now in Edinburgh, and was likely executed by Cock on the spot.

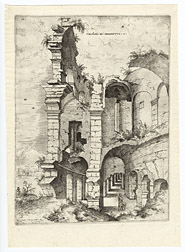

Looking inside

This etching shows a cross-section of the Colosseum, another view based on a drawing by Cock himself. It combines a glance upwards onto the upper Corinthian tier with a tunnelling view down into a radial basement corridor crossed by dark shadows. At the time as he was publishing his first series of ruins in Antwerp, Cock was also publishing maps―this etching, however, is oriented horizontally, making it more like the page of a book. The inscription "PROSPECTUS" alerts beholders that the image is a view, rather than a plan.

In the extreme lower left of the print, next to a date of "1550," there is a just-visible number, 1546, which, remarkably, has been effaced. Most likely this number is the date of the original drawing, which Cock erroneously transferred when he etched the plate.

Sculptural Subjects

Like buildings, antique sculptures in Rome were rarely preserved intact. This engraving is likely a copy of a 1550 print attributed to the Lorraine printmaker Nicolas Beatrizet, and shows an allegorical sculpture known as Marforio. Pendant to the famed Pasquino, the reclining Marforio was one of the "talking statues" of the sixteenth century. Disgruntled citizens would post written complaints on the marbles, denouncing civic injustice or, more often, mount anonymous critiques of the papacy.

Duchetti has excised some of the inscriptions that appear in earlier version of the print, such as that which appears a Florence copy of the Speculum. Missing both arms, lower legs, and the tip of its nose, Marforio was probably an allegory of the Tiber River. In the print, a youth at immediate left, dwarfed by the sculpture's huge bulk, energetically studies the Marforio with sketchbook in hand. The inscription at the center is even a semi-humorous "Marforiade," which, within the print has the effect of alluding to the very public character of the sculpture.

The Septizonium

This print records remnants of the so-called Septizonium (or Septizodium), a strange columnar structure erected on the south Palatine Hill in 203. Scholars disagree about the function of the building; some suggest it was intended as a greeting monument for visitors approaching Rome on the via Appia, to the southwest. In the print, weeds mantle the cragged top edges of the porches and ivy weaves in and out of the entablatures, yet the masonry walls are shown surprisingly intact. This state was not to last long: Pope Sixtus V destroyed the building entirely in 1588-9 to construct a new roadway.

In fact, despite the emergence of building conservation programs as early as the 1520s, more ancient Roman monuments were actually destroyed in the Renaissance than in preceding centuries. The papacy fully sanctioned digging for gems and sculptures on the Palatine, which irreversibly weakened many antique structures. Along with several architectural drawings from the 1570s, this print by Lafreri was one of only a few records of the Septizonium to survive.

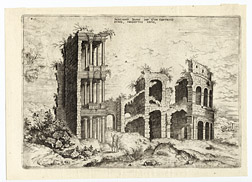

A Juxtaposition for Landscape's Sake

In this etching, Hieronymus Cock imaginatively conjoins two structures which lay nearly a mile apart from another in Rome, the Colosseum and the Septizonium. The siting of the buildings can be compared with, for example, Lafreri's print in A11. The twin monuments appear on a ruddy, lumpen hillock at the end of a roadway, where two onlookers point left and right. The pair functions as a surrogate for our own view onto the landscape, and rhymes visually with the gigantic buildings before them.

This detail of the Colosseum corresponds a drawing now in Berlin by the Dutch artist Marten van Heemskerck (1498-1574) which Cock might have known. At least in comparison to Duchetti (cf. A29), Cock here proves most interested in landscape effects rather than topographical accuracy. As in the other prints from the 1551 series, these ruins are depicted in what the Dutch called schilderachtig, or picturesque mode-less archaeological sites than pictorial motifs. As a publisher, Cock would have been well aware of the potential for ruins to appeal to collectors of art as well as those interested in Rome.

Along with other sketches this image was republished in three separate editions by Cock's firm in the Antwerp, Aux Quatre Vents (At the Sign of the Four Winds). The series went on to be re-printed in France and in Italy, and came to exert a lasting influence on landscape painting from mid-century, informing the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Veronese.

Antique time in the present

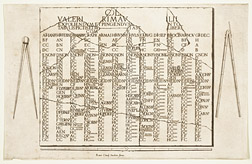

This fascinating engraving reproduces an ancient Roman calendar, etched into a tablet and discovered in 1547 by Bernadino Maffei, cardinal of Rome. Three feet by two feet, the plinth is shown astride three pairs of callipers, which indicate scale. Along the top row of the tablet, the months, or what the Romans called calends, are indicated before their name, topping twelve columns all starting with the letter K. Interesting is the inscription "NON" which can be seen falling on the fifth or seventh day of each month; this was an abbreviation for nonus (ninth), a ritual day when the moon reached its first quarter phase.

Duchetti's print is remarkable for presenting the calendar as an object rather then just information. Carefully delineating the tablet's cracks and its roughened edges, the image is characteristic of an increasing interest among Renaissance antiquarians in recording extra-literary aspects of inscriptions.

The famous Antwerp printer Plantin copied the print in 1574, but the tablet itself was soon broken up and lost. A fragment survives today in the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

Sources for art

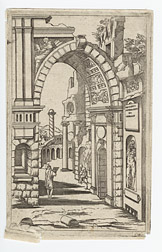

In this engraving an artist stands beneath a fanciful ruined arch, engrossed in the reliefs above. This print was one of many published by Androuet du Cerceau designed by Leonard Thiry. Thiry worked in Antwerp, where he could have known Hieronymus Cock, and might have influenced Cock's decision to concentrate on picturesque ruins as a print theme. Like Cock's Colosseum views (e.g. B212), Thiry's prints invariably show ruins dotted with draughtsmen in action. Published in many subsequent editions this print was also used for intarsia designs in France and Southern Germany.

A Sculpture Garden

Scholars are unclear whether this print describes an actual sculpture garden, as its inscription suggests. It is likely based on a drawing by Marten van Heemskerck; Hieronymus Cock, the publisher, carefully notes his role as "printer" (excu) rather than inventor of the print in italics at lower left. Draped male and female marbles, a sarcophagus, column drums, entablatures, and a half-buried capitals lean against a masonry wall and lay scattered in the foreground. We know that this print was engraved by Lucas van Jan van Doetecum, a sibling team famed for their ability to transcribe painterly shades of light and dark using a mixed process of etching and engraving.

The design makes little distinction between fragments of architecture, sculpture, or funeraria, and the single bearded bystander, who sits, right arm raised, on a collapsed column shaft is almost indistinguishable from the other mutilated sculptures themselves.

Taking Ruins Home

In this engraving the Flemish artist Hendrick van Cleve has extracted motifs from ruined Roman monuments and inserted them into a fantastic Alpine landscape. Cleve made hundreds of drawings in Rome and nearby Tivoli in the early 1550s. These were later excerpted in prints published by the Collaert family. The hemicylindrical temple and obelisk were completely new motifs for many Northern European art viewers, and would have been know solely though reproductions like the Speculum.

The copper plate for this print survived well into the seventeenth century and was restruck several times. Flemish inventories list it as a page from a runenboeck, or Book of Ruins, suggesting the potency of the idea in popular imaginings of Rome.