The Belvedere Cortile: An Early Museum of Ancient Sculpture

Prints and the museum experience

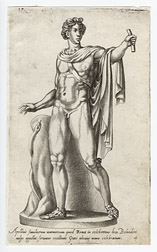

The Apollo Belvedere was a mainstay of Cardinal Giuliano delle Rovere's sculpture collection before he became Pope Julius II, and was one of the early statues to be placed in the Belvedere Cortile, where it is documented from 1508. The statue court in the Belvedere Cortile was a proto-museum that displayed some of Rome's most famous large-scale ancient statues in a garden setting that recalled the antique viridarium. Because the collection belonged to the Pope and was kept within the Vatican complex (where most of these statues are still displayed today), the statues were not as easily accessible to visitors as other outdoor statues. However, Bramante's spiral staircase did provide entry to the raised, walled space of the garden from the outside, and numerous surviving drawings of the statues by artists prove that the space was semi-public. Ironically, prints helped to enhance rather than erode the aura of exclusivity and preciosity which hovered around the Belvedere statues.

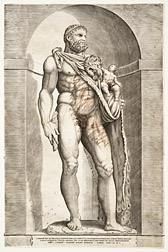

In this engraving from Antonio Lafreri's Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the Apollo statue is shown raised on a pedestal and fitted into a niche. This niche with a simple horizontal molding is a standard backdrop which appears on other prints of Belvedere statues published by Lafreri, such as the Laocoon (A107) and the Hercules Commodus (A94). Lafreri's engravers seem to have reserved this treatment for objects in prestigious collections, as a means of simulating the experience of viewing from a vantage point below the statue. This staging recalls the reverential viewing experience which our culture associates with museum displays. Lafreri's prints remind us that such display strategies originated in the Renaissance. The engraver's ingenuity in this regard is evident, for the niche device is the only feature of the print which was not appropriated from an earlier engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi (Bartsch 331). Niches shown in Lafreri prints do not always replicate the installation, and are often standard and conventionalized. However, in this case, Lafreri's engraver depicts the installation with some accuracy by including the trellis in schematic form. This trellis in the recess behind Apollo is corroborated by other artists such as Francisco de Hollanda.

This print postdates Montorsoli's 1532-33 restorations to the statue, which included changes to the angle of the right forearm, alterations to the tree trunk, and the addition of new hands. Lafreri's reliance on an earlier print by Marcantonio Raimondi is the most plausible reason Apollo appears in unrestored form.

The Latin inscription informs us of the object's nature as a marble sculpture ("ex marmore sculp"), and its location in the pontifical palace in the area commonly known as the Belvedere ("in palatio pont in loco qui vulgo dicitur Belveder"). The name "Apollo" does not appear, most likely because this statue was famous enough for immediate recognition. The statue is believed to be a Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic bronze.

For discussion of the statue's iconography and restoration, see the next image.

Prints as records of restorations

The Apollo Belvedere was one of the most famous and best preserved ancient statues of Renaissance Rome. This print appeared in several editions of Giovanni Battista de' Cavalieri's Antiquarum statuarum urbis Romae, which was first published in 1561. Cavalieri is an interesting figure in the history of print publishing because he was both engraver and publisher, and most of his plates were based on his own drawings rather than copied from other prints.

Over the centuries, the Apollo Belvedere garnered praised as a model of ideal human proportions, masculine beauty, and poised movement. The statue depicts Apollo, who, like his twin sister Diana, often utilized arrows. With his right foot advanced and his right arm recoiled, he is probably shown in the moment directly following the launching of an arrow from the (purported) bow supported by his extended left arm. His gaze seems to follow the arrow to its target.

When excavated, Apollo Belvedere was missing only the left hand and fingers from the right hand. The statue was displayed for over two decades in the Belvedere statue court prior to its 1532-33 restoration by the sculptor Giovanni Montorsoli. As recorded by drawings and prints, Montorsoli removed the strut between the right hip and right wrist, raised a portion of the tree trunk as structural compensation for the lost strut, and provided a new left hand holding part of a bow. Montorsoli's inclusion of the bow fragment was an educated guess derived from the accessory quivers which Apollo carries. In addition, Montorsoli mutilated part of the statue, removing the intact right forearm to install his new right forearm and hand. This perplexing decision is consistent with one known aspect of Renaissance antiquarianism: the willingness to sometimes destroy or irremediably alter ancient artifacts. In a 1924 restoration, a decision was made to reverse Montorsoli's restorations (except for the strut). Because Montorsoli had removed the original right forearm, the statue today appears with more missing parts than when it was first excavated. This print accurately documents the appearance of the statue after Montorsoli's restorations. It also preserves the general appearance of the statue prior to the reverse restoration of 1924.

The image of Apollo with arrows and a supposed bow was an excellent addition to the Virgilian iconographical program of Julius II's statue court (see next image). According to the Aeneid, Apollo, in his role as oracle, proclaimed to Aeneas that Rome would be founded by his descendants. Also, as protector to Emperor Augustus, Apollo shot the first arrow of the Battle of Actium in which Augustus defeated Antony and Cleopatra. Apollo was thus a fitting emblem of the continuity Julius II wished to establish between his own era and the Golden Age of Imperial Rome.

The Hercules Commodus and the Julian program for the Belvedere Cortile

In a fortuitous concordance of desires and events, Julius II expanded his collection by acquiring exceedingly rare, freshly unearthed ancient statues. The statue of Commodus as Hercules was excavated in 1507 from the garden of a house in Rome's Campo dei Fiori. Julius II moved quickly to purchase the statue, and it was no sooner given a prominent role in the visual program of the Belvedere statue court. Recent interpretations of Julius II's statue collection explore the iconographic significance of the selection and installation of these objects. At the same time, the gradual process of acquiring statues subsequent to the designing of the statue court resulted in an ad hoc, revisable "program."

Julius installed the Hercules statue near the entrance to the statue court. Above the entrance appeared an inscription from Virgil's Aeneid: "procul este profane" ("begone, ye uninitiated"). In the Aeneid, these words are uttered by the Cumaen Sybil to Aeneas as he enters the underworld. After escaping from burning Troy, Aeneas descends to the underworld where he is greeted by his father Anchises, who prophesies the founding of Rome by Aeneas' descendants and identifies the future heroes of Roman history. The thematic relationship between the Hercules statue and the entrance inscription also lies with the Aeneid: in the Aeneid, Aeneas is described fleeing Troy in Herculean attire.

Julius' 1506 acquisition of the statue of the Trojan priest Laocoon (see A107) seems to have provided the impetus for the statue court's Virgilian program. Understood within the context of Julian ideology, the statue court not only projected a sense of pride in Roman history and artifacts, but more importantly articulated Julius' aims of "Cesaro-Papismo"―that is, the notion of the Pope as heir to the Roman emperors and herald of a new Golden Age. References to the Aeneid also resonated with panegyrists, who drew connections between Julius' name and that of Aeneas' son Ascanius, who became known as Julus after leaving Troy.

In Julius' time, Tommaso Inghirami, prefect of the Vatican Library, identified the statue as the Emperor Commodus in the guise of Hercules on the basis of ancient texts stating that Commodus liked to appear in the guise of Hercules. Lafreri's inscription maintains this identification, and also mentions the small child held by Hercules, but does not explain the child's role. As first suggested in the nineteenth century, this statue probably depicts Hercules and not an emperor portrait. The child could therefore be Hercules' son Telephos.

This engraving bears marks of censorship, as someone has used heavy pen lines to obliterate the genitalia of both Hercules and Telephos. These hatched and cross-hatched lines appear to form the contours of (additional) animal skins.

In the inscription, Lafreri identifies himself as "sequani", a Latin name for one of the Gallic tribes. This learned reference vaunts the cosmopolitanism of our French publisher who operated in Rome.

Translating sculpture into two dimensions

The Belvedere Torso was first recorded in Rome in the fifteenth century, and most likely entered the papal collection in the 1530s during the papacy of Clement VII. This over life-sized fragment, believed to represent Hercules, attracted fame in the sixteenth-century with Michelangelo's well-documented fondness for its muscular form. Michelangelo adapted the Belvedere Torso in numerous works such as the painted ignudi on the Sistine Ceiling and the sculpture of Day for the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici. Michelangelo's adaptations suggest a variety of ways in which Renaissance artists drew upon ancient sculptural sources, including reuse in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional media.

Prints facilitated Renaissance artists' reuse of sculptural prototypes into two dimensions by rendering volume and mass pictorially through hatching and other graphic means. However, the translation into two dimensions usually engendered a loss of visual information. In this instance, the engraver Francesco Aquila anticipated the problem by including two separate views of the torso on the same sheet. These two views can be characterized as the informational view and the artistic view. The left "informational" view shows the front of the torso and the animal pelt, transcribes the signature ("Apollonius, son of Nestor, Athenian") by the Greek sculptor on the base. and registers all of the places where limbs and body parts are truncated. The right "artistic" view captures the part of the statue that most appealed to artists: the expressively contorted musculature of the back. The statue's twisting pose which encourages viewing from all sides may further explain Aquila's decision to provide two views. The Italian inscription markets this feature of the print ("mostrato in due vedute"), and we might entertain the idea that this was a smart purchase for the buyer of these single-leaf prints, almost like obtaining two prints for the price of one.

In addition to its non-frontality, the Belvedere Torso differs from other famous works of the Belvedere collection in its marked state of fragmentation. Whereas some of the Belvedere statues had missing parts restored in the Renaissance, the Belvedere Torso remained unchanged. It is possible that the fragmentary and anonymous features of the torso made it easier for artists to imagine new uses.

The Vatican complex and the Borgo

This etching is by Israel Sylvestre, an artist from Lorraine who specialized in topographical views of France and Italy. Sylvestre traveled to Italy three times between 1638 and 1654, recording landscapes and architecture of Rome, Florence and Venice. These images were then sold in France by his publisher, Israel Henriet. This etching depicts Saint Peter's basilica and the circular structure of the Castel Sant'Angelo on the right bank of the Tiber River.

Although the Belvedere statue court is not visible, the etching does show Bramante's three-storey loggia immediately to the right of the basilica. The purpose of this long wing extending to the north was to connect the Apostolic Palace to the 1487 villa of Innocent VIII located on the northern periphery of the Vatican Hill. Another loggia structure (constructed after Bramante's death) ran parallel to the one shown here, and the large open space between these two wings formed a courtyard or "cortile" that was used for tournaments and other celebrations, as seen in A67. Bramante's architecture solved the problem of balancing the higher terrain on which the Villa Belvedere sat by providing a steady horizontal line in the roof of the loggia, and by designing ramps and terraces that created gradual transitions between the ground levels. Built adjacent to the Villa Belvedere, the Belvedere statue court was a courtyard within a courtyard located at the northeast end of Bramante's cortile.

Sylvestre's etching presents an idyllic scene of human activity. A silhouetted figure at left shoots a hunting rifle aimed at ducks in the water, two nearby figures rest on the shore, and a fishing boat lingers in the middle of the river. A typical feature of Sylvestre's etchings, inherited from the manner of the Lorraine artist Jacques Callot, is the shadowy delineation of foreground areas with dense calligraphic lines to frame the scene. The asymmetrical placement of the foreground tree directs the eye in a rightward movement in order to appreciate the expansive vista of the Vatican architecture as it runs parallel to the water. These compositional choices nevertheless undermine topographical accuracy―in reality, St. Peter's is farther back from both the river bank and from the Castel Sant'Angelo, and there were many more buildings (including the Egyptian obelisk) in the borgo which would have obstructed the view of St. Peter's from across the river.

In terms of architectural history and urban planning, Sylvestre's etching dates from circa 1650, a short time before the construction of Bernini's majestic colonnade for St. Peter's square, which began in 1656 (see A82).This print documents another project by Bernini, the bell towers for the façade of St. Peter's. On the south end of the façade, one of the towers appears, its construction seemingly halted. The towers, begun in 1638, were ordered destroyed in 1646 by Pope Innocent X after their weight was determined to have caused cracks in the structure. Thus, Sylvestre's view appears to show the south tower not in construction, but rather being dismantled.

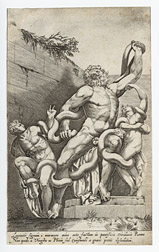

Laocoon at arm's length

Claude Duchet, known as Claudio Duchetti in Italian, was a French publisher in Rome who inherited part of the publishing house of his uncle, Antonio Lafreri upon his 1577 death. Duchet continued the enterprise of the Speculum, making copies of Lafreri plates to replace inventory that was lost when part of the business went to another relative, Etienne Duchet. Here, Claude Duchet's engraver copied in precise detail a print engraved by Beatrizet and published by Lafreri. This Beatrizet print was itself copied from an earlier print of the Laocoon group by Marco Dente (Bartsch 353), with the only differences being the background and Laocoon's restored right arm. The continuity with Dente's print demonstrates how engravers sometimes used previous engravings as pictorial templates, rather than copying directly from a statue or monument in Rome. Another example of this practice is Lafreri's Apollo Belvedere (A96), based on a print by Marcantonio Raimondi. Copying an earlier print was convenient because it provided instant solutions to issues like vantage point, presentation, and the modeling of forms.

The right arm on the central figure of Laocoon was missing when the statue was excavated in 1506. In the course of its complex history, numerous solutions for the position of the arm were proposed, and some of these were attached only to be subsequently removed and replaced by others. Aspects of the restoration history are still debated or uncertain. In 1532-33, Montorsoli created a terracotta addition which restored the arm. Either Montorsoli's restoration or another sixteenth-century arm made for the Laocoon is shown in Duchet's print. This arm holds a diagonal, extended position. An antique arm believed to be the original was unearthed in 1906, and was attached to the statue in 1942. This antique arm (which remains on the statue today) differs from the Renaissance restoration in that the forearm is bent backwards rather than outstretched.

Duchet's print shows that at this time the statue was unevenly restored, for even though Laocoon's arm is replaced, his two sons both have missing parts, as they did upon excavation: the right arm of the child on the left is missing, and the right fingers of the child on the right are missing. Clearly, Renaissance restorers, like modern scholars, first focused their attention on the arm of Laocoon, which is so crucial to interpreting the expressive tenor of his struggle.

For discussion of the discovery and iconography of this statue, see the next image.

Laocoon continued

Following in the wake of successful publications by Antonio Lafreri and Giovanni Battista de' Cavalieri, this print comes from Lorenzo della Vaccaria's Antiquarum Statuarum Urbis Romae, a compilation depicting ancient statues in private and public Roman collections. Vaccaria employed Cherubino Alberti, Orazio de Santis and several other artists as engravers. This print is related to a plate in Cavalieri's publication, except that the Laocoon statue is here shown in reverse with a different background. The stage of restoration shown in this print approximates a c. 1591 drawing by Hendrick Goltzius, which depicts Laocoon with a restored arm, the youngest son with a restored arm, and the eldest son with three missing fingers. This print and the Goltzius drawing are records of a second restoration that restored the son's arm sometime after the first restoration of Laocoon's arm (this first restoration is documented in A121).

The 1506 unearthing of the Laocoon was a momentous event enshrined in collective memory. It was discovered on January 14 in the vineyard of Felice de'Freddi on the Esquiline hill. Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo came to inspect the statue, and Sangallo was said to have immediately recognized the group as the work described by Pliny. According to Pliny, it was sculpted by Hagesandrus, Polidorus, and Athenodorus of Rhodes, was carved from a single piece of marble, and was "of all paintings and sculptures, the most worthy of admiration." Sixteenth-century antiquarians, upon realizing that it was made of several marble blocks, began to question whether it could be the same statue Pliny described. The statue Pliny revered was already likely a marble copy after a bronze original, and thus continual questions about the dating and authorship of this statue have not eclipsed its reputation.

According to the story of Laocoon's death in Virgil's Aeneid, Laocoon was a Trojan priest who rightfully suspected the wooden horse offered by the Greeks, warning the Trojans not to bring it into the city. He pierced the horse with his spear to see if Greeks were inside, saying "I fear the Greeks, even when they bring gifts." Athena, who sided with the Greeks, sent two serpents to kill Laocoon and his sons in order to prevent him from stopping the Greek treachery. The statue depicts Laocoon and one of his sons being overtaken by the snakes, while the older son begins to break free. This moving representation of a struggling man as he succumbs to death has elicited much discussion and praise as a consummate work of art, particularly among eighteenth-century German scholars.

Julius II purchased the statue within a month of its discovery, and the Laocoon group established the Virgilian program for his statue court. As noted by Hans Brummer, within the Romanocentric ideology of Julius II, the story of Laocoon was understood as a portent for the Fall of Troy, which eventually led to the founding of Rome.

The inscription calls attention to the connection between the statue and the writings of Virgil and Pliny, which contributed to the statue's fame. The wall shown behind the statue is an imagined setting, for the statue was actually installed in an architectural niche.

Installation and Interpretation

This image depicts the Vatican Cleopatra, a second-century Roman copy of a Greek original of the Hellenistic period. The print is from Lorenzo della Vaccaria's Antiquarum Statuarum Urbis Romae, which first appeared in 1584. Dating each individual print is a complicated matter, because many plates were reused across different editions. This print comes from the edition issued in 1621, when numbering was introduced (see the number 47 in the lower left). Vaccaria's publication takes its title, conception, and many of its printed images from Giovanni Battista de' Cavalieri's publication. In this instance, Vaccaria's engraver has wholeheartedly copied the entire image from Cavalieri. The main differences are the number and the background composed of fine horizontal striations. This kind of copying was common in the unregulated publishing industry of Renaissance Rome.

About a decade after its excavation, Julius II purchased the Cleopatra statue in 1512 from Gerolamo Maffei, a member of a prominent Roman family of collectors. The statue was installed in the Belvedere Cortile within a shallow niche and equipped with a fountain mechanism. The fountain installation was a humanist conceit related to contemporary antiquarian interest in water nymphs. Even though the statue was identified as the dying Egyptian queen Cleopatra because of the snake bracelet around her arm (Cleopatra committed suicide by poisoning herself with an asp), the nymph association was also central to Renaissance interpretations. Indeed, the print's inscription acknowledges both identifications. In the eighteenth-century, it was found that the statue depicts neither Cleopatra nor a nymph, but rather Ariadne lying on the shores of Naxos after her abandonment by Theseus.

This print records a later installation of the statue which retained certain elements, such as the fountain, from Julius' II installation. In 1551 during the papacy of Julius III, the statue was transferred from its niche in the statue court to the indoor "Stanza della Cleopatra," a small room at the northern extremity of the eastern corridor which opened onto the statue court. The walls and ceiling of the room were richly decorated with stucco, ornamental grotesque imagery, and frescoes by Daniele da Volterra of Old Testament subjects connected with water. As shown here, the statue was set into an architectural fountain framework consisting of a large scallop shell on the ground level and two terms supporting an upper mantelpiece decorated with a winged mask. The statue crowned this superstructure, and the grotto-like middle area between the herms appears to be where the fountain water flowed. This construction mirrored contemporary developments in landscape architecture, and reinforced the statue's nymph iconography by evoking nymphs' traditional dwelling place, the grotto.

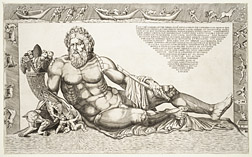

The Tiber River God

This print depicts the nude statue of the River God Tiber holding a cornucopia and a broken udder (restored in the eighteenth century), resting atop a base that was carved with ridges to represent water. The statue was unearthed in January 1512 near Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. Like several other recent discoveries, it was quickly acquired by Julius II and integrated into the Belvedere Cortile setting. Arriving soon after the Cleopatra statue, it too was eventually equipped with a fountain to highlight the aquatic theme.

This print was engraved by Nicolas Béatrizet for Lafreri's Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae. The fictive frieze shown along three borders of the image shows the human activity such as commerce, transport, fishing and swimming which occurred in the river. It also depicts the types of fauna which could be observed along the banks of Rome's river, including sheep, foxes, and horses. The frieze is a clever way of showing the scenes that are carved in relief on the sides and back of the statue base, which would not be visible in this view. There were several well-known antique statues in Rome with similar pose and appearance. The elegantly tapered inscription in Roman capitals provides information that was possibly intended to help the viewer differentiate this statue, both visually and thematically, from the other statues of river gods. For example, the inscription mentions the presence of Romulus and Remus, the twin brothers who founded Rome, along with the she-wolf that nurtured them with breast milk. These figures appear beneath the cornucopia held by the river god. Beyond the information it offers, the inscription serves to guarantee quality and accuracy: in the last sentence, the viewer is assured that Lafreri printed this image in copper with precision ("ad amussim excusum").

In terms of graphic effect, this print is indeed executed with remarkable precision and skill. The frieze and inscription enliven the white area behind the horizontal statue. Also, there is a careful visual alternation of gray and crisp white tones, particularly in the small negative spaces around the god's limbs.

Unlike its pendant the Nile (see next image), the Tiber is one of the few statues that left the Belvedere collection permanently. It was removed by Napoleon in 1797, and is now displayed in the Louvre.

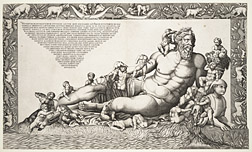

Pendant prints for pendant statues

In 1513, the year after the discovery of the Tiber statue, the Nile was unearthed at the same site, and was purchased by Leo X, the successor to Julius II. These companion statues were mounted on identical large plinths and were displayed facing each other in the middle of the Belvedere statue court. This arrangement made sense, because the head of the Nile statue is oriented to the right, whereas the Tiber is oriented to the left, and the two statues would have been nicely aligned when placed facing each other. The two statues are also very close in scale: both are colossal statues over three meters long.

It is fitting that Béatrizet employed the same formula for his prints of the Tiber (see previous image) and the Nile, because even in antiquity they were treated as pendants, as indicated by the close proximity of their burial sites. Thus, we see in this print the same approach employed in the Tiber print: a border frieze derived from the actual reliefs on the sides and back of the statue base, and an extensive inscription in Roman capitals with tapered formatting.

The Nile-specific iconography includes the local attribute of the sphinx beneath the deity's arm, and the exotic animals such as crocodiles and hippos in the border frieze. The putti climbing on and around the god's body also relate to the locale: Pliny described a famous statue with sixteen figures of children, which represented the sixteen cubits the Nile needed to rise during the rainy season in order to irrigate the land. The Nile statue is probably a Roman copy of the Alexandrian statue described by Pliny.

Some of the putti shown here are missing heads or other body parts. This reflects the statue as it appeared in the Renaissance. The putti were not restored until the eighteenth century under Pope Clement XIV.